Aircraft engines can be classified by several methods. They can be classed by operating cycles, cylinder arrangement, or the method of thrust production. All are heat engines that convert fuel into heat energy that is converted to mechanical energy to produce thrust. Most of the current aircraft engines are of the internal combustion type because the combustion process takes place inside the engine. Aircraft engines come in many different types, such as gas turbine based, reciprocating piston, rotary, two or four cycle, spark ignition, diesel, and air or water cooled. Reciprocating and gas turbine engines also have subdivisions based on the type of cylinder arrangement (piston) and speed range (gas turbine).

Many types of reciprocating engines have been designed. However, manufacturers have developed some designs that are used more commonly than others and are, therefore, recognized as conventional. Reciprocating engines may be classified according to the cylinder arrangement (in line, V-type, radial, and opposed) or according to the method of cooling (liquid cooled or air cooled). Actually, all piston engines are cooled by transferring excess heat to the surrounding air. In air-cooled engines, this heat transfer is direct from the cylinders to the air. Therefore, it is necessary to provide thin metal fins on the cylinders of an air-cooled engine in order to have increased surface for sufficient heat transfer. Most reciprocating aircraft engines are air cooled although a few high powered engines use an efficient liquid-cooling system. In liquid-cooled engines, the heat is transferred from the cylinders to the coolant, which is then sent through tubing and cooled within a radiator placed in the airstream. The coolant radiator must be large enough to cool the liquid efficiently. The main problem with liquid cooling is the added weight of coolant, heat exchanger (radiator), and tubing to connect the components. Liquid cooled engines do allow high power to be obtained from the engine safely.

The inline engine has a small frontal area and is better adapted to streamlining. When mounted with the cylinders in an inverted position, it offers the added advantages of a shorter landing gear and greater pilot visibility. With increase in engine size, the air cooled, inline type offers additional problems to provide proper cooling; therefore, this type of engine is confined to low- and medium-horsepower engines used in very old light aircraft.

Many types of reciprocating engines have been designed. However, manufacturers have developed some designs that are used more commonly than others and are, therefore, recognized as conventional. Reciprocating engines may be classified according to the cylinder arrangement (in line, V-type, radial, and opposed) or according to the method of cooling (liquid cooled or air cooled). Actually, all piston engines are cooled by transferring excess heat to the surrounding air. In air-cooled engines, this heat transfer is direct from the cylinders to the air. Therefore, it is necessary to provide thin metal fins on the cylinders of an air-cooled engine in order to have increased surface for sufficient heat transfer. Most reciprocating aircraft engines are air cooled although a few high powered engines use an efficient liquid-cooling system. In liquid-cooled engines, the heat is transferred from the cylinders to the coolant, which is then sent through tubing and cooled within a radiator placed in the airstream. The coolant radiator must be large enough to cool the liquid efficiently. The main problem with liquid cooling is the added weight of coolant, heat exchanger (radiator), and tubing to connect the components. Liquid cooled engines do allow high power to be obtained from the engine safely.

Inline Engines

An inline engine generally has an even number of cylinders, although some three-cylinder engines have been constructed. This engine may be either liquid cooled or air cooled and has only one crank shaft, which is located either above or below the cylinders. If the engine is designed to operate with the cylinders below the crankshaft, it is called an inverted engine.The inline engine has a small frontal area and is better adapted to streamlining. When mounted with the cylinders in an inverted position, it offers the added advantages of a shorter landing gear and greater pilot visibility. With increase in engine size, the air cooled, inline type offers additional problems to provide proper cooling; therefore, this type of engine is confined to low- and medium-horsepower engines used in very old light aircraft.

Opposed or O-Type Engines

The opposed-type engine has two banks of cylinders directly opposite each other with a crankshaft in the center Figure 1. The pistons of both cylinder banks are connected to the single crankshaft. Although the engine can be either liquid cooled or air cooled, the air-cooled version is used predominantly in aviation. It is generally mounted with the cylinders in a horizontal position. The opposed-type engine has a low weight-to-horsepower ratio, and its narrow silhouette makes it ideal for horizontal installation on the aircraft wings (twin engine applications). Another advantage is its low vibration characteristics. |

| Figure 1. A typical four-cylinder opposed engine |

V-Type Engines

In V-type engines, the cylinders are arranged in two in-line banks generally set 60° apart. Most of the engines have 12 cylinders, which are either liquid cooled or air cooled. The engines are designated by a V followed by a dash and the piston displacement in cubic inches. For example, V- 1710. This type of engine was used mostly during the second World War and its use is mostly limited to older aircraft.

Radial Engines

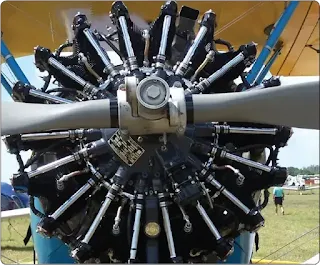

The radial engine consists of a row, or rows, of cylinders arranged radially about a central crankcase. [Figure 2] This type of engine has proven to be very rugged and dependable. The number of cylinders which make up a row may be three, five, seven, or nine. Some radial engines have two rows of seven or nine cylinders arranged radially about the crankcase, one in front of the other. These are called double-row radials. |

| Figure 2. Radial engine |

[Figure 3] One type of radial engine has four rows of cylinders with seven cylinders in each row for a total of 28 cylinders. Radial engines are still used in some older cargo planes, war birds, and crop spray planes. Although many of these engines still exist, their use is limited. The single-row, nine-cylinder radial engine is of relatively simple construction, having a one-piece nose and a two-section main crankcase. The larger twin-row engines are of slightly more complex construction than the single row engines. For example, the crankcase of the Wright R-3350 engine is composed of the crankcase front section, four crankcase main sections (front main, front center, rear center, and rear main), rear cam and tappet housing, supercharger front housing, supercharger rear housing, and supercharger rear housing cover. Pratt and Whitney engines of comparable size incorporate the same basic sections, although the construction and the nomenclature differ considerably.

|

| Figure 3. Double row radials |

RELATED POSTS